Next – Project

“Blood Mountain is at the helm of something unique: something challenging and above all, relevant and stimulating to contemporary art and practice. It is a model that extends the artist to his or her limits. It is a studio experience providing context, dialogue, proposition, process, tension and ideas. Blood Mountain is a space to enact consciousness, a place to think and work”.

– Asim Memishi, February 2011

Exhibition

Tenets of Impermanent Value

23 February to 03 April 2011

Venue: Blood Mountain, Vérhalom utca 27/c, Budapest 1025, Hungary

The artist’s mission during the residency was to explore Hungary’s cultural history, Blood Mountain’s architectural identity and his own fascination with the legacy of the Ottoman Empire in Central and Eastern Europe.

The exhibition, Tenets of Impermanent Value was a play between the old and the new: the theme of Ottoman occupation and contemporary construction; traditional methods and materials contrasted with contemporary street signs; and the artist’s own dual identity as a new-world Australian with old-world Albanian roots.

The exhibition occupied three spaces. Space 1 acquainted the visitor with an objective position; focusing on the mechanics of construction practices and methodologies of knowledge gathering and transfer used by the Ottoman Empire. Space 2 showcased Memishi’s personal interpretation of historical events with visual tropes to Budapest’ built environment today. Space 3 paid tribute to the domestic life of war and the role of individual lives, which was underlined by a significant literary work and showcased in the studio space, where the artist lived and worked during his stay at Blood Mountain.

Memishi’s residency was accompanied by an education programme for primary school students. Tenets of Impermanent Value was Blood Mountain’s second exhibition and Memishi’s first solo show in Hungary.

Survey

The starting point of Memishi’s exhibition was artistic research about the Ottoman Empire’s occupation of Central Europe, along with the context and history of the Blood Mountain’s location. Located in a neo-baroque villa on a hilltop district of Budapest Hungary, Blood Mountain was positioned in a street named after a violent Ottoman battle, which represented Hungary’s complex history and cultural heritage. It is the area where the Ottoman Empire conquered the local Hungarians and settled for over 150 years (1541-1699). In sharp contrast, the surrounding area was colloquially known as Rosehill; a name attributed to Gül Baba, who was a peaceful Sufi poet and key member of the Ottoman occupation. Gül Baba was renown locally for his friendly nature and signature style, which included wearing a fresh rose in his turban each day. He lived and died within walking distance of the Blood Mountain villa and his tomb remains a rare example of permanent Ottoman architecture in Hungary. Today, it is widely known as the most north-western site of the Muslim pilgrimage, it is meticulously maintained and ornamented with rose bushes under the jurisdiction of the Turkish government. The Ottoman Empire’s legacy at Blood Mountain was the key focus of Asim Memishi’s artistic research as Artist-in-Residence in February 2011. Australian-born Memishi’s Albanian heritage and interest in Ottoman history has been a reoccurring source of inspiration for his art and life.

The exhibition followed the building’s structure and Space 1 set an architectural tone by presenting two site-specific artworks, made with traditional techniques of the building industry. A mural drawing (190 x 260cm) was created by a chalk-covered string stretched to maximum friction and like a guitar string, plucked on to the wall surface. Designed within a rectangular perimeter, the 450 striations derived from a single point to create a dynamic geometric pattern comparable to the visual texture of hand-spun wool and to the mechanical visual vocabulary of op art by Bridget Riley.

The second artwork was a minimalist triangular installation, comprised of a long piece of white string and a custom-made brass plumb hung on its vertical axis. Fixed in the corner of Space 1 and penetrating in to the next room, the work enticed visitors to continue exploring unchartered territories, as the Ottomans once did at this very location. The above techniques are affordable and reliable building techniques still used in construction today to achieve a near-perfect perpendicular 90-degree angle. They were standard techniques that helped create significant permanent structures during the Ottoman epoch in Central Europe, including Blood Mountain’s building, Gül Baba’s tomb and Budapest’s many public baths, which are the lasting legacy and important daily rituals for residents and visitors of the city.

Siege

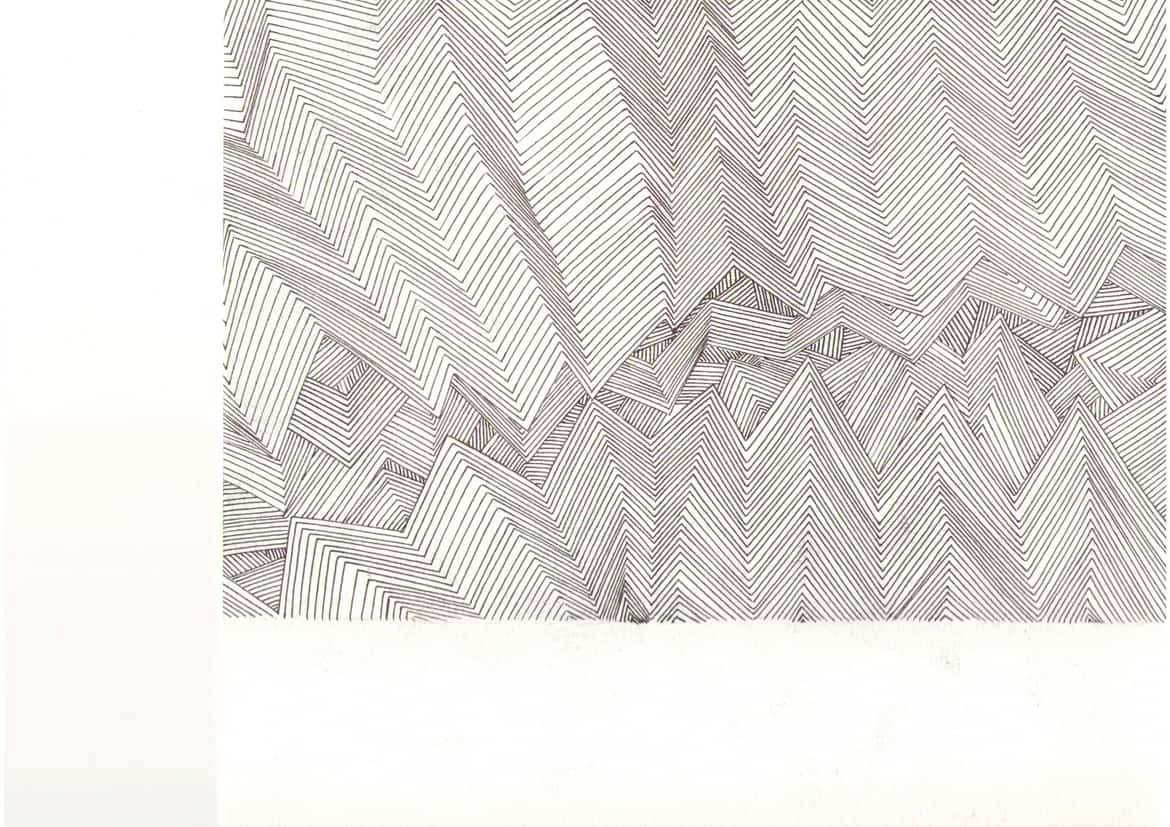

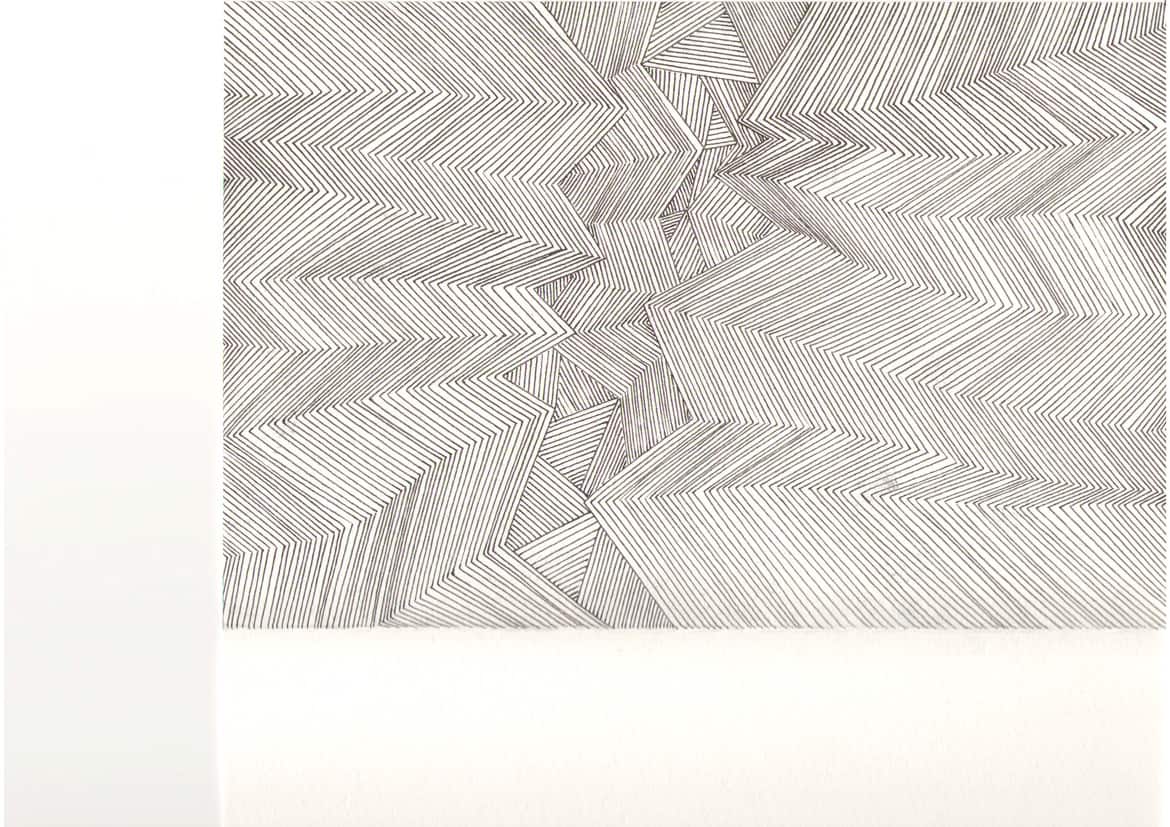

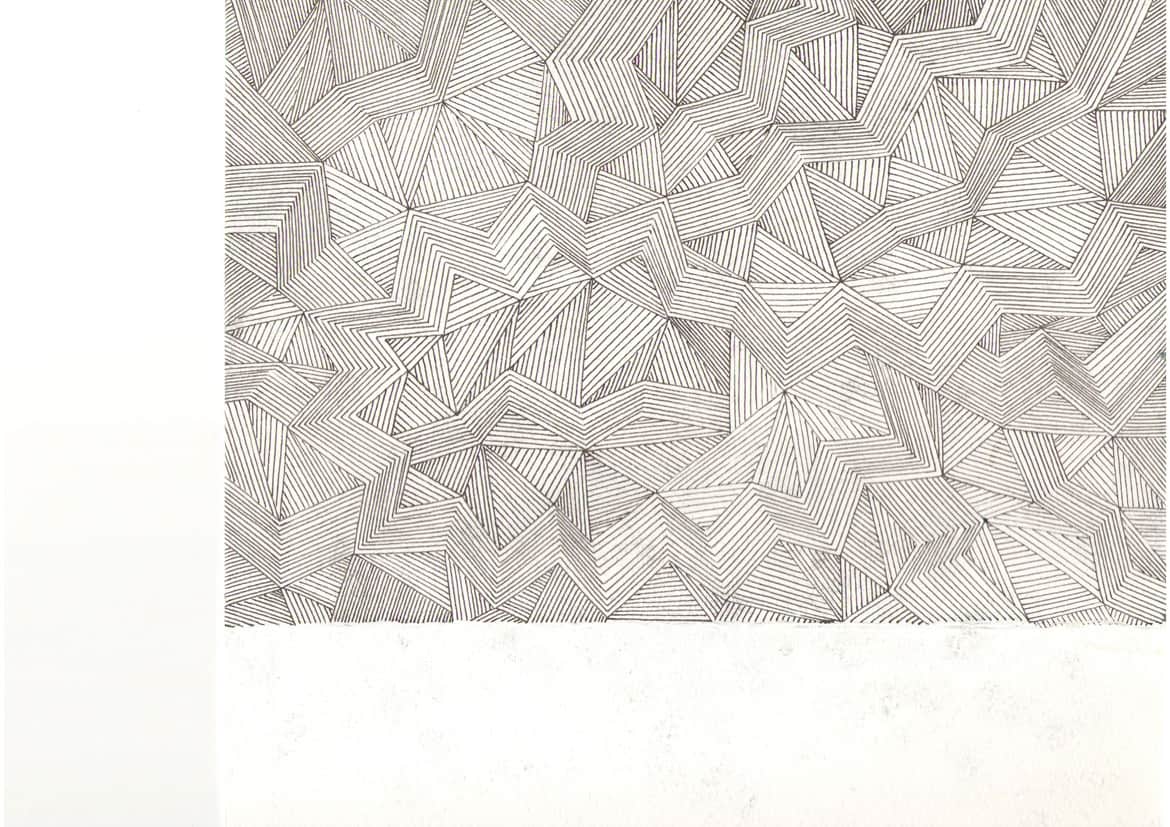

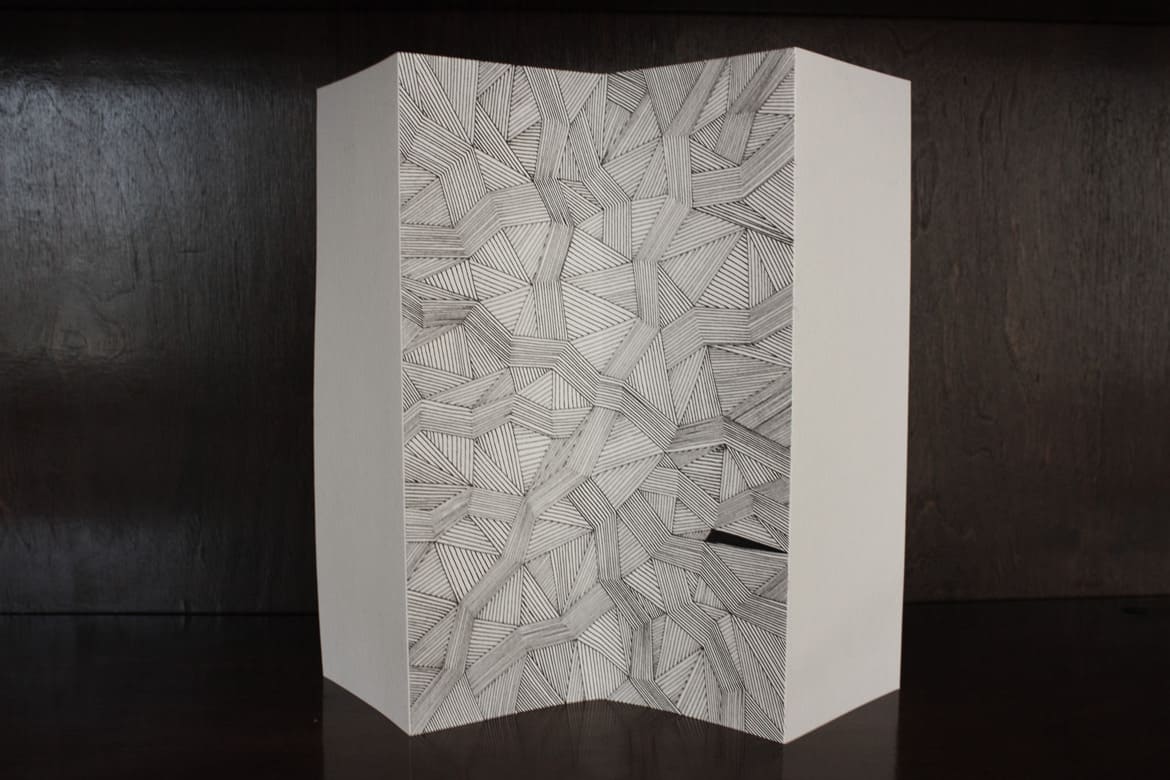

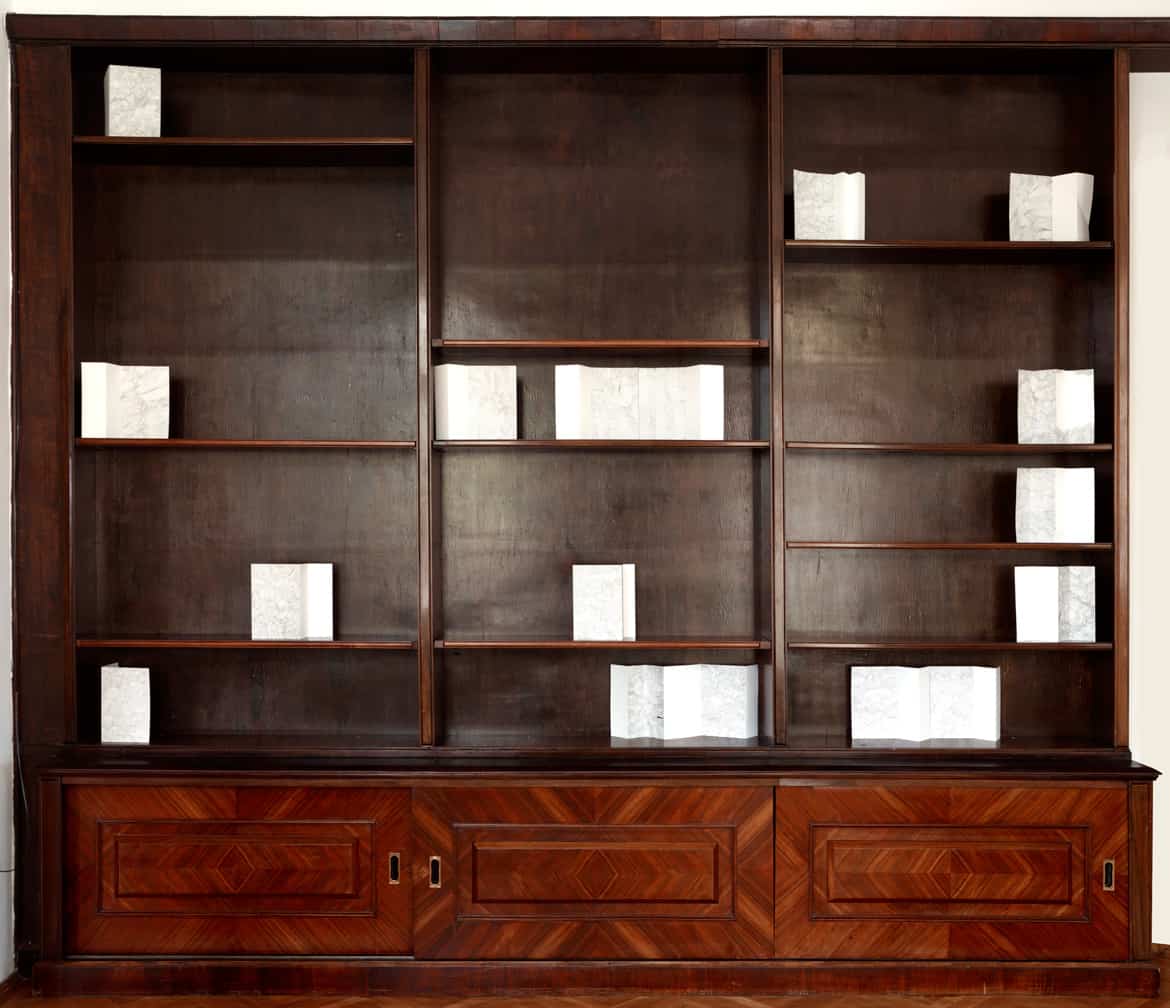

Space 2 showcased a selection of pen on paper drawings on a built-in bookshelf. 24 abstract line drawings with unique folding patterns were arranged asymmetrically, where the negative space found in the artworks and on the bookshelves become as relevant as the intricate shapes set out by the line drawings and their placements. Conceived free-hand and in a moderate format comparable to the intimate size of traditional novels, the drawings became a personalised form of cartography: symbolic interpretations of the lands, borders and nations, which have defined the region of Central and Eastern Europe for generations.

The context of the bookshelf was symbolic: commonly understood as a site for knowledge, the artworks were taken as ciphers for books i.e. as symbols of power and continued Memishi’s fascination with the relationship between authority and resistance. An important reference for this word was “The Siege”, a novel published in 1970 by Albanian writer, Ismail Kadare and exploring the Albanian-Ottoman war of the early 15th century, which is widely recognised as the birth of Albanian nationalism and growing resentment towards the then omnipresent Ottoman Empire.

Kadare’s novel provides detailed descriptions about the Ottoman Empire’s unique method of occupying foreign lands: first through negotiation, where diplomats armed with architects and chroniclers such as Gül Baba were sent to new towns to negotiate tax payments with local authorities and document the land and people in writings and drawings. When this method proved insufficient, a military occupation ensued. Nomadic villages, packed with domestic life (plush interiors, harems of women, children and servants) and concerns about food and sanitation were a crucial part of the daily reality, alongside battle tactics and weaponry.

An acrylic on canvas (210 x 200cm) hung adjacent to the bookshelf and depicted a red-and-white measuring stick, traditionally used to survey land. Six three-dimensional reproductions of this utensil were positioned throughout the exhibition. The painting also depicted the reproduction of a street utility sign, commonly used in Budapest’s contemporary built environment.

The term ‘T150’ refers to the location of Rosehill, as categorised by the local land authority and ‘4.8’ explains the depth in meters needed to access utility services, in this case electricity, which is represented by the colour red. Symbolising power as a sign system of everyday live, the artwork entered in to dialogue with the contemporary notions of Memishi’s practice.

Settlement

Space 3, the final destination of the exhibition, was a symbolic reproduction of a traditional Ottoman tent, a semi-permanent domestic structure which would have stood in the place of Blood Mountain 500 years earlier. Presented in the domestic setting of the artist’s studio, where Memishi lived and worked for the duration of the artist-in-residence, the subjectivity of this space transported the narrative of the artist’s endeavour to a more private and personal state.

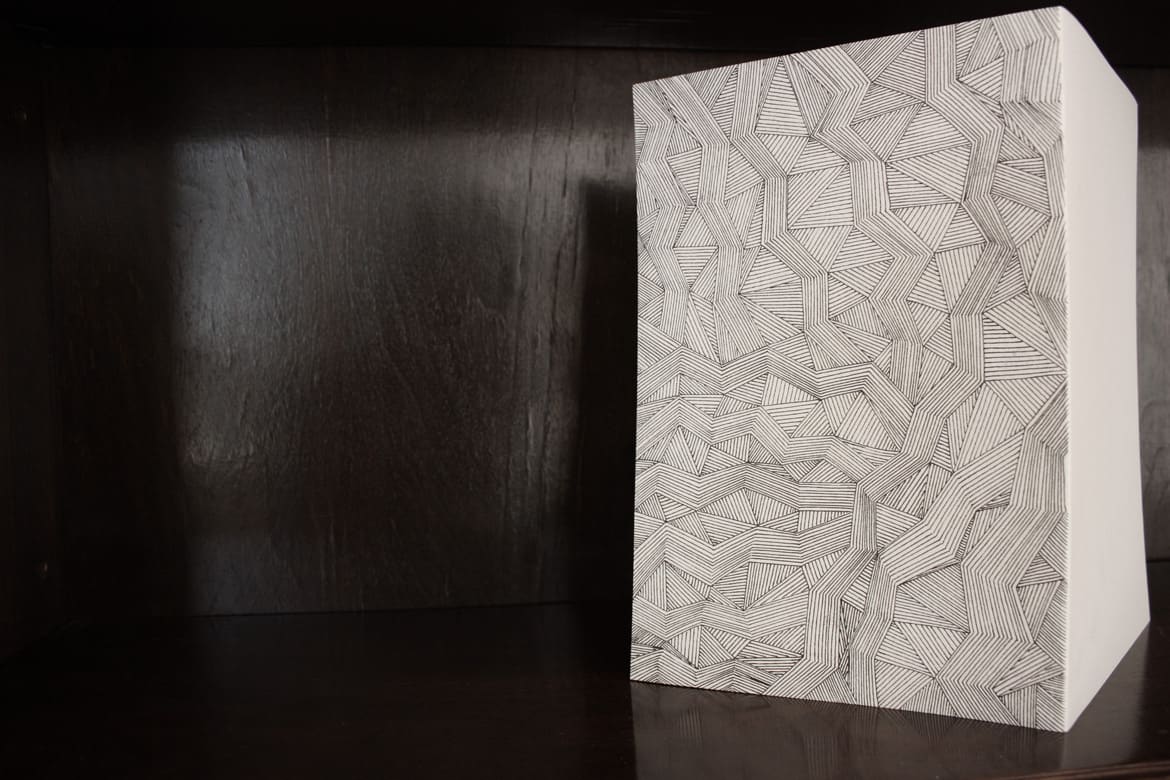

The installation was accompanied by an ink on canvas piece (200x210cm), hang on a neighbouring wall and lit from below. The intricate shadows and reflections cast by the light source engulfed the artwork and the surrounding walls, and drew attention to the villa’s Habsburg era architecture. And yet it reminded the viewer, that the Ottoman occupation of 150 years came before Hungary’s subsequent invasions by the Habsburgs (1867-1917), Germans (1938-1945) and Soviets (1946-1989).