Next – Project

Curated by Jade Niklai

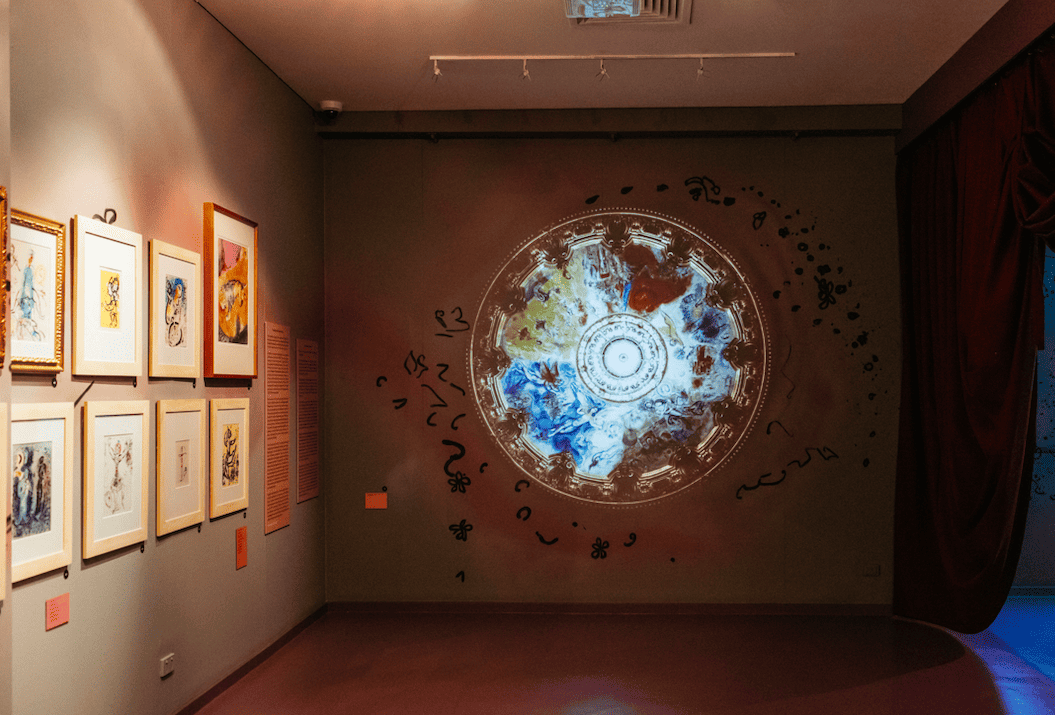

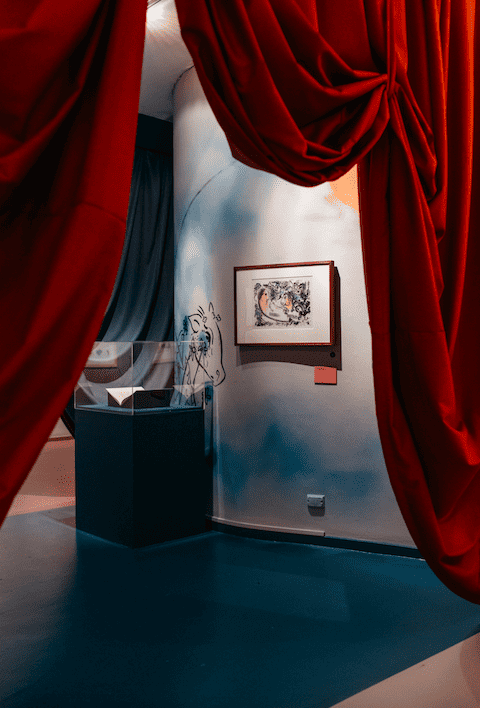

Designed by Anna Tregloan

07 June – 10 December 2023

Jewish Museum of Australia

26 Alma Road, St Kilda 3184

Melbourne, Victoria Australia

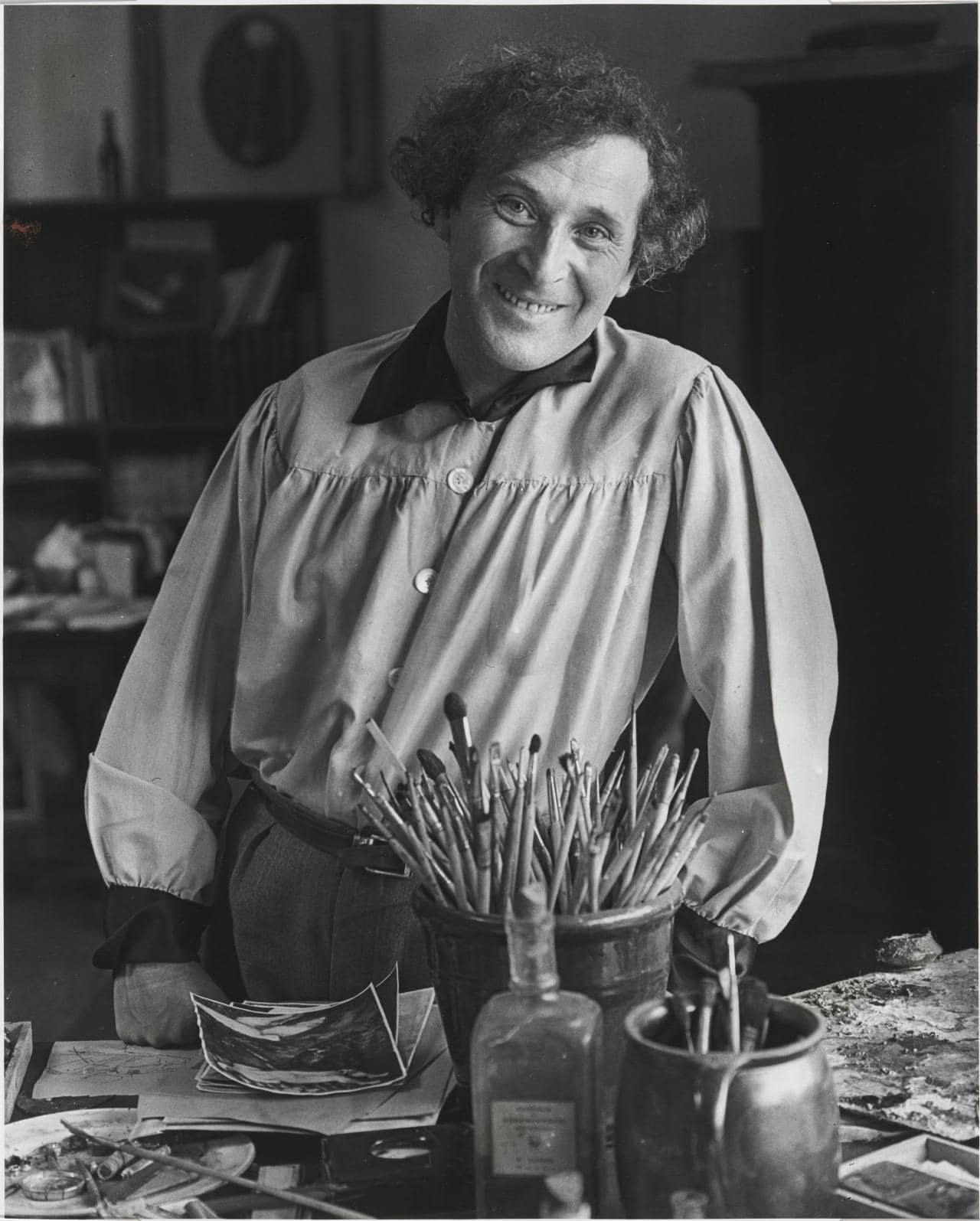

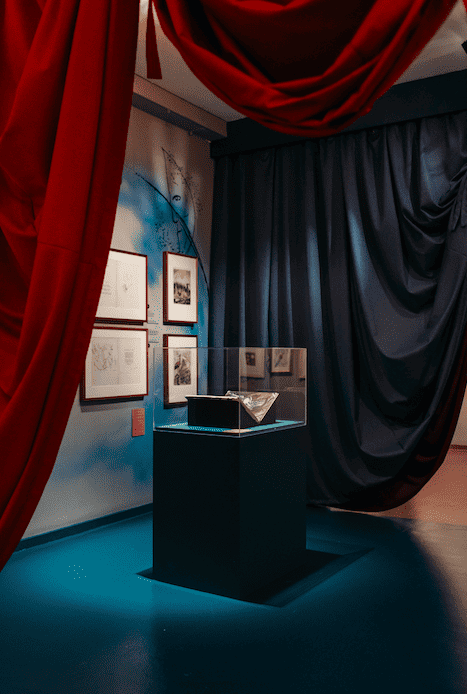

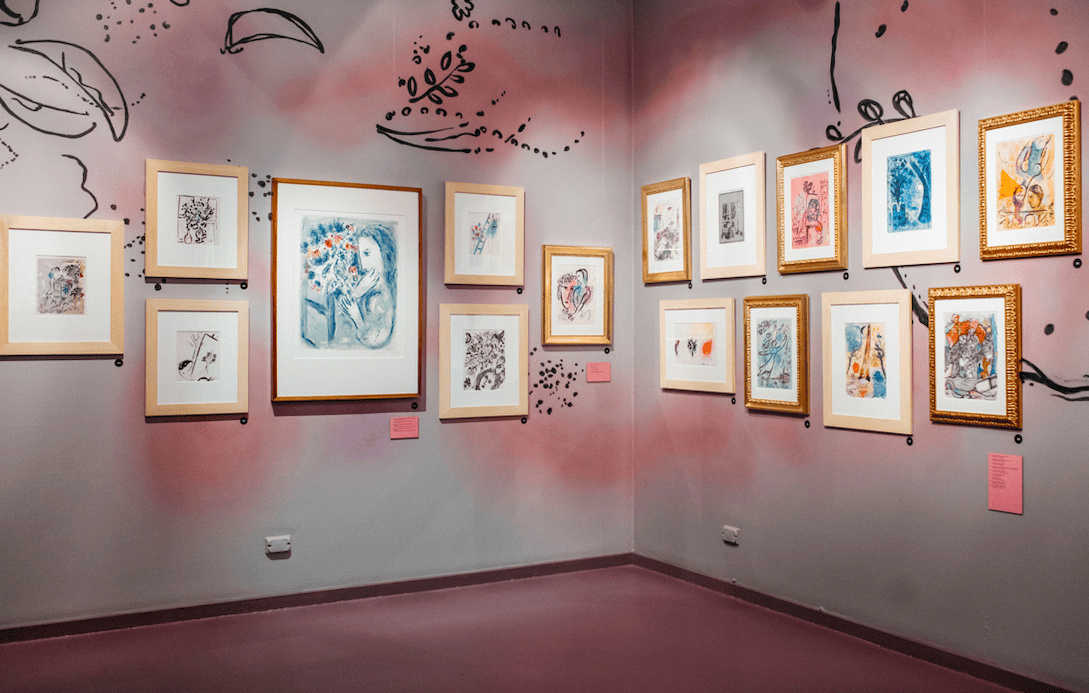

CHAGALL examines Marc Chagall’s practice in Printmaking, Poetry and Public Art with the display of over 120 artworks selected from Australian public art collections and private holdings in Europe. All artworks have been authenticated by the Chagall Estate in Paris.

It is the first time Chagall’s extensive oeuvre is viewed through this curatorial prism and as the exhibition is organised thematically, not chronologically, it is advisable to begin this virtual tour with an overview of his biography.

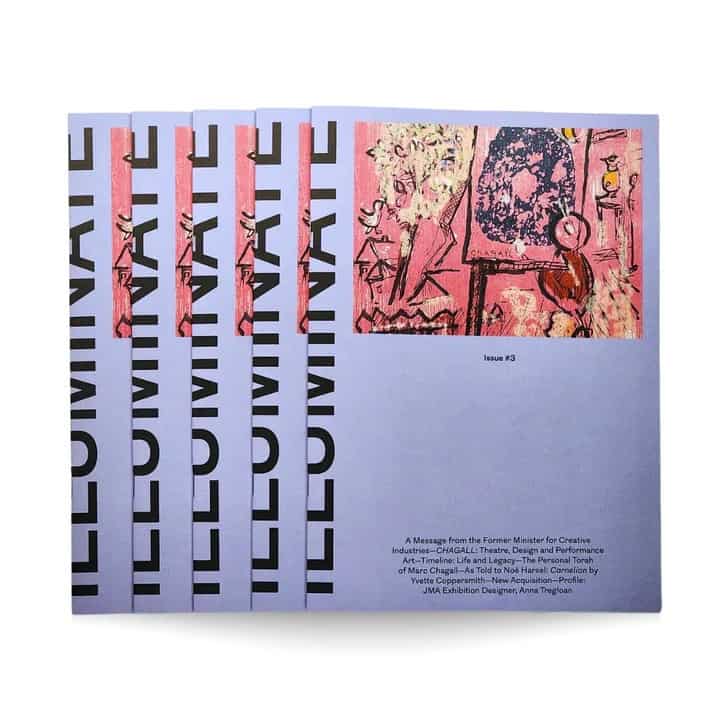

CHAGALL is the Museum’s second solo exhibition on the artist, following Dr Helen Light AM, the inaugural director’s 1995 exhibition, Chagall and the Bible. It is also the launch of the Museum’s new Contemporary Art Commission by Melbourne-based visual artist, Yvette Coppersmith, whose solo exhibition is realised as an artistic response to CHAGALL.

Exhibition

Language and Literature

Language and literature occupied a central role in the art and life of Marc Chagall. Born and raised in a tight-knit Jewish community in Tsarist Russia’s Pale Settlement, Yiddish was Chagall’s first language and arguably, his emotional language for life.

Chagall read the Bible and wrote poetry in his native tongue throughout his life. The foundation of his 30-year relationship with Bella Chagall (née Rosenfeld) was a shared love of literature, and it is widely documented that she read to him in several languages while he worked.

In Paris (1911–1914) Chagall learnt to speak and write French and during two sojourns in Berlin (1914 & 1922) picked up conversational German. However, he refused to speak English during his American years of exile (1941–1948) and despite a growing interest from the international artworld, hr never gave interviews in English. In 1924 while living in Paris, Chagall half-jokingly revealed:

“Once I used to write Yiddish well, but since I became a Goy, I write with mistakes or in Russian-Jewish.”

Chagall remained connected to old Russia through family life, literature and language. While his memory was tinged with nostalgia and ambivalence, he stayed faithful to his mindset and artistic practice, which stood in stark contrast to other émigrés and looked to the future with concerted efforts to adapt and assimilate.

Known in childhood as ‘Moishe’, he converted to ‘Movsha Shagal’ (with several Russified and Germanised variations, including ‘Schagaloff’ and ‘Chagaloff’) in 1907, when he first moved to St. Petersburg to study. The first known written document with the name ‘Marc Chagall’ appears in the exhibition catalogue of the Salon des Indépendants (1912), his first group show in Paris.

Printmaking and Poetry

Chagall arrived in Berlin in 1922, aged 35 with an unpublished autobiography. A chance meeting with Paul Cassirer, a local art dealer and publisher of luxury books, led to the commissioning of etchings for his autobiography and began the artist’s journey in printmaking.

The text, originally written in Russian, was an homage to Chagall’s parents and his rural Chasidic childhood. Delays and disagreements over the translation gave Chagall time to move away from literal representations of his text and develop new visual content. He began working in dry point, which enabled him to draw directly with a steel needle on a polished plate. He painted simple, bold brush strokes, dramatic chiaroscuro contrasts and varied shading techniques, which created compassionate scenes of provincial shtetl life.

In 1931 Cassirer issued an album of 20 etchings in an edition of 110 under the title, Mein Leben (My Life). There was no accompanying text, Chagall and Cassirer could not agree on the translation. The publication ignited Chagall’s life-long passion for printmaking, giving him a new medium beyond oil painting to expand his magical visual vocabulary and creative compulsion for storytelling.

Chagall’s illustrations for My Life are widely recognised by critics as his last expressionist works and mark his departure as an Eastern European artist towards a more Western European reception and pictorial language. While the book remains contested as a historic resource, it has been translated to many languages and enjoys regular reprints.

Book as Artistic Medium

Chagall’s collaborator in printmaking was Ambroise Vollard, a Parisian art dealer and publisher, who motivated the Chagalls to relocate from Berlin to Paris in 1924. On Vollard’s commission and with a burning love of literature, Chagall worked tirelessly in 1924–1925 to illustrate Nikolai Gogol’s Russian novel, Les Ames Mortes (Dead Souls), 1842. Chagall related to Gogol’s experience of working in self-imposed exile and it is documented that Bella read the novel to him while he hammered away at the copperplates.

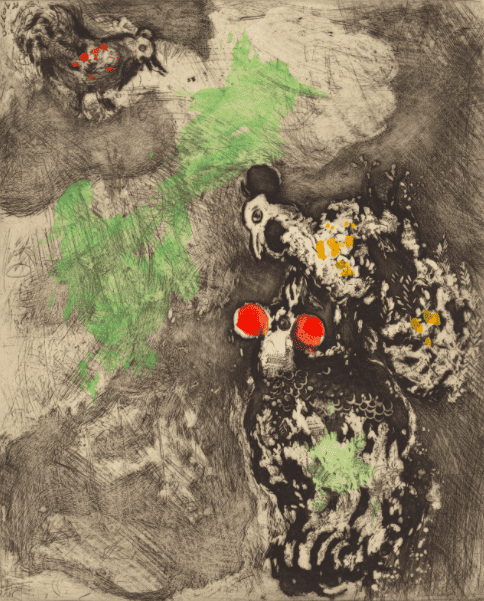

The etchings, while depicting playful and absurd scenes of provincial life in the Russian Empire, also reveal Chagall’s artistic evolution in printmaking. Two significant print collaborations followed between Chagall and Vollard and feature prominently in this exhibition.

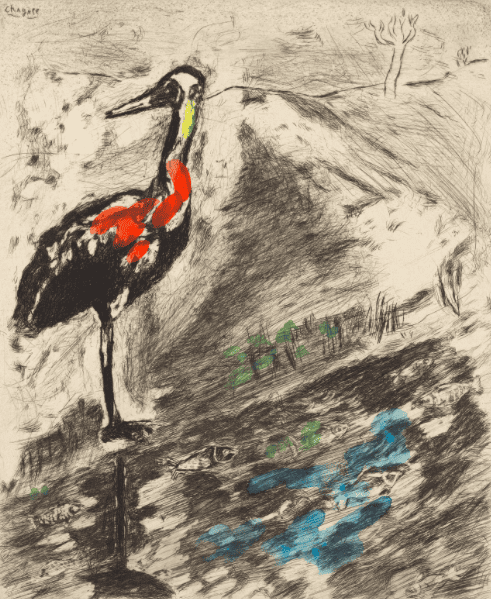

In the mid 1920s, determined to assimilate in Paris, Chagall embraced landscape painting: an artistic tradition linked with upper-class values and popularised at the time by the works of Claude Monet and Paul Cézanne. He illustrated a new edition of Jean La Fontaine’s Les Fables (The Fables), 1668–1694: a humorous collection of morality tales set in the French countryside with phantasmagorical animal protagonists. This work resonated with Chagall’s love of satirical literature and understanding of provincial life.

The Chagall-Vollard collaboration continued with the Bible series, featured in this exhibition.

Vollard’s tragic death from a car accident in 1939 left Chagall’s illustrations for Dead Souls, The Fables and the Bible series unpublished. It was only after World War Two that these three seminal illustrated books were released by the Paris-based Greek publisher, Tériade.

Chagall recalled in later life:

“Something would have been lacking in my life, if I had not at a certain stage become involved in engraving and lithography.”

Paris and Passion

Two decisive epochs underline Chagall’s practice in Paris.

1911–1914

Chagall first embraced the vibrant and visceral atmosphere of Belle Époque Paris in 1911. His arrival coincided with the opening of the Salon des Indépendants, which launched Cubism. He moved comfortably among literary and artistic circles and lived at La Ruche, a creative commune in Montparnasse with neighbours including artists Alberto Giacometti, Fernand Léger and Soutine, and writer-poets Guillaume Apollinaire and Blaise Cendrars.

Despite the daily imposition of starvation and homesickness, Chagall felt that he belonged. As a Jew, he was no longer treated as a second-class citizen, but as an immigrant among other minorities. His art flourished. Only the imminent outbreak of World War I made him return to Vitebsk.

Of this period, Chagall later remarked:

“I seemed to be discovering light, colour, freedom, the sun [and] the joy of living for the first time”.

1923–1933

Chagall returned to Paris in 1923 as a family man and concentrated on illustrated book projects and landscape paintings. His wife, Bella’s affluent upbringing, impeccable French and love of socialising, ensured the household as an epicentre of art and ideas. Their circle included the Parisian artworks figureheads, Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Claire and Robert Goll; alongside Russian writers and poets, Vladimir Nabokov and Pavel Ettinger. French, Yiddish and Russian were spoken daily.

For the first time Chagall’s art embraced objective beauty (flowers and landscapes) and affectionate couples, which he showed with increasing nudity and often alongside Paris landmarks, such as the Eiffel Tower, Pont Neuf and Notre Dame. Despite Andre Breton’s claim during this epoch, that Surrealism is indebted to Chagall’s early dream-like paintings, the artist refuted this association. His practice evolved toward classical flatness and design: Chagall was becoming a modernist European artist.

His earlier oil paintings began to rise in value, and with Vollard’s book commissions, the Chagalls enjoyed a comfortable bourgeois life. The family’s efforts to assimilate during this period laid the foundations for Chagall’s future legacy as one of the great French artists of the 20th Century.

Theatre and Performance

Marc Chagall’s lithographs and book illustrations of harlequins, acrobats and circus animals, embody the nostalgia, longing and tragicomedy of his early efforts in theatre and performance in post-revolutionary Russia.

Chagall’s first theatre project was a cabaret in Moscow (1918). When the actors appeared with green face paint; he was dismissed. His second effort was the Theatre of Revolutionary Satire, which he commissioned as Cultural Commissar of Vitebsk: a short-lived political post he accepted after the Bolshevik Revolution. 1919–1920 Chagall delivered ten comedy performances in the town’s main square to entertain and deliver propaganda to 200,000 Red Army soldiers.

Disillusioned with politics and arts administration, Chagall moved next to the Moscow Jewish Theatre where he worked as stage set and costume designer on three state-funded pantomimes. In one month, he realised seven monumental artworks and given the theatre’s modest scale and the design’s monumental ambition, the project was dubbed “Chagall’s Box”. It claimed instant critical and popular success; yet seen as too individualistic by Soviet authorities, Chagall was not paid and once again fired. He never worked in a Russian theatre again.

Chagall’s depiction of circus performers is broadly interpreted as a precursor to his figurative Biblical works and reflects his love of both ‘high’ and ‘low’ arts. In old age Chagall recalled fond childhood memories of a travelling circus in Vitebsk and in 1927 he enthused:

“[Charlie] Chaplin seeks to do in film what I am trying to do in my paintings…he is perhaps the only artist today I could get along with without having to say a single word.”

Public Art

Cultural Commissions

Opera Garnier, Paris

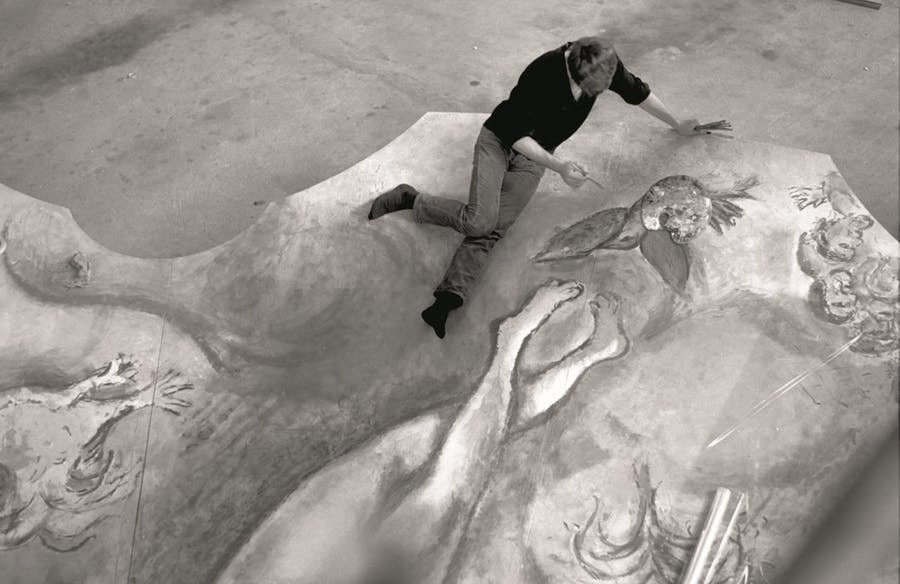

Chagall’s ceiling design for the Paris Opera House was his first permanent public art commission.

In 1960 André Malraux, then Minister of Culture, attended a stage production designed by Chagall. Hugely impressed, he commissioned Chagall during the intermission to redesign the ceiling. Scandal broke out that a Russian emigré was trusted with such a prominent national heritage site. After much debate and compromise, Chagall was obliged to produce 12 custom-sized canvases, instead of painting directly onto the wall.

The final design, covering 250 square metre canvases and weighing 250 kilograms, showcases 12 scenes from Chagall’s favourite operas and landmarks in Paris (Eiffel Tower, l‘Arche de Triomphe, Opéra) and Russia (Orthodox church spires of Vitebsk, cupolas of Moscow buildings).

To circumvent the terror threats made on his life because of this project, Chagall worked in hiding for years. The riot police supervised the installation.

Chagall’s vibrant and visionary design, which finally opened in 1967, matched the original neo-baroque building, commissioned by Napoleon III and designed by Charles Garnier. Chagall at last succeeded as a theatre designer and was accepted by the French art establishment.

United Nations & MET Opera, New York

The same year, Chagall also realised in New York a stained-glass window for the UN Headquarters and designed 39 extravagant curtains and 121 costumes for the MET Opera’s production of Mozart’s Magic Flute. Two large oil paintings were further commissioned by the MET and still greet visitors at its main entrance.

Religious Commissions

Chagall’s return to Europe at the end of World War Two marked the beginning of an unlikely artistic epoch.

The death of Bella Chagall in 1944, his wife of 30 years, marked his loss of connection to Jewish Russia. He understood that his art – fuelled by memory of provincial shtetl life – was in danger of becoming pastiche and nostalgic. He responded with a remarkable pivot.

Church commissions: Europe & United Kingdom

Chagall’s first religious art commission was at Notre Dame de Toute Grâce, a church in Haute Savoire already boasting artworks by Matisse, Léger and Bonnard. Confronted by its Christian context, he consulted many influential Jews, including Israeli President, Chaim Weizmann. With no objections, Chagall accepted the project as the first of many stained-glass windows he designed in the UK, France, Switzerland and Germany.

For the next 20 years Chagall worked on major projects we call today ‘public art’: walls in public spaces, windows and ceramic surfaces in churches, as well as stage set designs, curtains and ceilings. Chagall never charged for religious commissions. Lithography and book illustrations supplemented his income during these years.

While Chagall’s personal life had become secular, his art took on multi-faith spirituality. Church spires, seen in the backdrop of his early paintings, were now replaced by permanent public art commissions at Christian institutions. His spiritual fluidity and religious public art commissions present one of the great conundrums of his prolific career. Yet, Chagall’s most ambitious religious artwork and the only one to commemorate Judaism, is situated at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

The Hadassah Windows

In 1959 Marc Chagall was approached by Hadassah, The Women’s Zionist Organization of America, to create a public artwork for the Abbell Synagogue at the new Ein Kerem Hospital of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

With the famous words: “What took you so long? I’ve been waiting my entire life to be asked to serve the Jewish people”, Chagall accepted the commission to design twelve stained-glass windows.

Born in Eastern Europe with a Chasidic upbringing, Chagall was familiar with Jewish customs, traditions and rituals. His art often incorporated Biblical themes and represented Jewish life, alongside modernist art motifs and ideas. Despite living a secular life since The Shoah, Chagall approached the commission with the deep conviction of a Jewish artist. He understood it as his contribution to the Jewish people and the newly established State of Israel.

Chagall refused payment, but insisted on choosing the style, subject matter and design.

Marc Chagall’s Hadassah Windows, displayed at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, represent the 12 sons of the biblical patriarch, Jacob.

Each composition is a modernist rendition of animal-life, food and nature and embodies the individual characteristics, blessings and attributes of the 12 sons, as described in the Old Testament. Respecting the Second Commandment, no idols were depicted. Chagall refused payment for the commission, but insisted on choosing the style, subject matter and design.

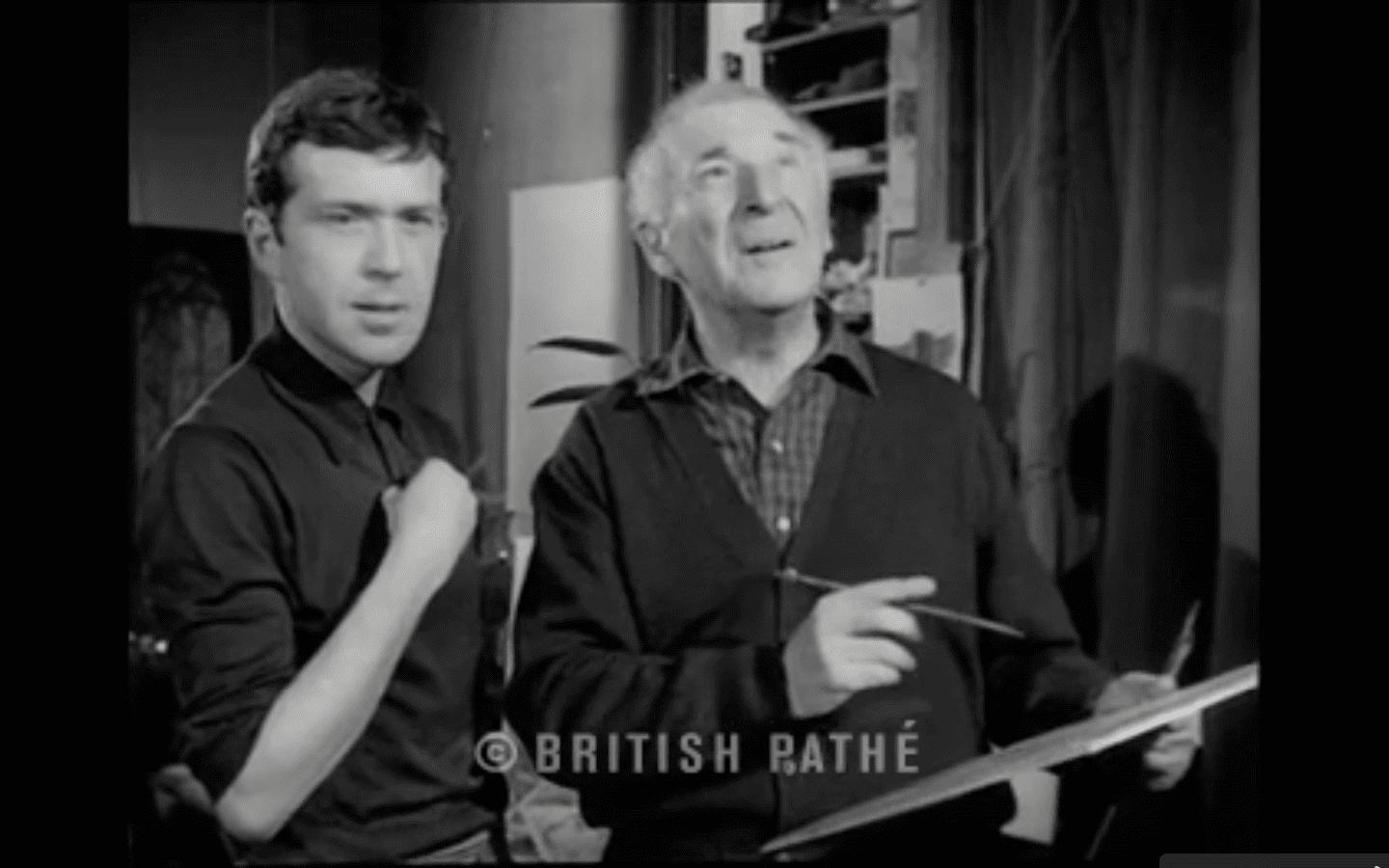

Chagall began work on the project in 1959 with small pen and ink drawings, transferring them to coloured sketches, collages and detailed gouaches. His assistants, Brigitte and Charles Marq, then translated the 2-D design to a 3-D artwork at the Atelier of Jacques Simon in Reims France.

Each window consists of 12 sections (300 H x 250 W cm each), made from over 50 sheets of coloured glass. Chagall colour painted, etched, scratched, blew, rolled and cut each sheet to create a rich array of colours and patterns. Acid was also applied to produce white areas and lighter tones, allowing the artist to ‘paint’ like watercolour. This innovative technique revolutionised stained-glass design.

The windows were completed in 1961 and prior to transport, shown at the Louvre. It was the first time a living artist exhibited in the National Art Museum. It then travelled to The Museum of Modern Art in New York, before reaching its destination in Jerusalem. Chagall attended the opening on 6 February 1962.

During the Six Day War (1967), the Hadassah window entitled, Zebulon (1960) was shot. When contacted by phone for instructions as the conflict was unfolding, Chagall quipped:

“You look after the wounded, and I will take care of the windows.”

Contrary to conservation standards, the bullet hole was filled with white glass to represent the ‘wound’ and to stand as a permanent reminder of the conflict.

The Hebrew University’s Medical Centre remains the only place in Jerusalem to treat patients of all faith and culture, and its Abbell Synagogue – where the Hadassah Windows are on permanent display – continues to serve as a place for prayer and spirituality for patients, staff and visitors.

Stills from ‘Marc Chagall Works on a Series of Stained Glass Windows’ (1961, 1:14 mins), part of the CHAGALL exhibit. Courtesy British Pathé. To watch click here.

Among Chagall’s many stained-glass window designs, displayed in prominent churches and cathedrals of continental Europe and the UK, the Hadassah Windows are his sole public art commission attributed to Judaism.

The Hadassah Windows were the first of many artistic collaborations between Chagall and the French artist-duo, Brigitte and Charles Marq. Their partnership revolutionalised the production and appearance of stained-glass window design (see earlier post and short documentary in the exhibition). Chagall’s use of Rheims Cathedral, where France’s kings and cardinals were historically anointed, as a 1:1 model for his Hadassah Window design, highlights his complicated relationship with Judaism and Catholicism.

While the Hadassah Windows were realised during Chagall’s later period and characterised by his disillusionment with faith following World War Two, it testifies to his unflinching belief in the human spiritual and widely regarded as one of the most important Jewish artworks of all time.

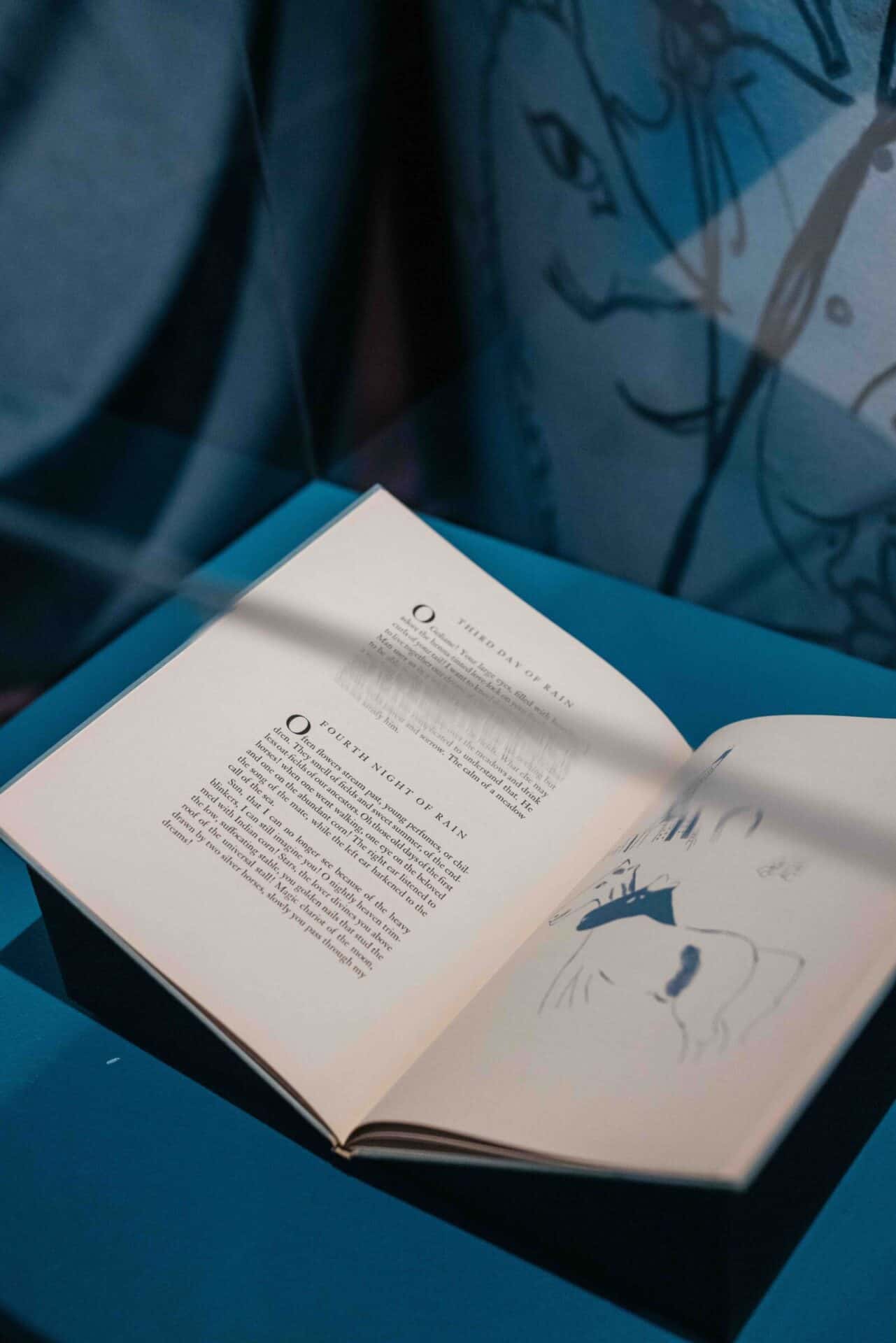

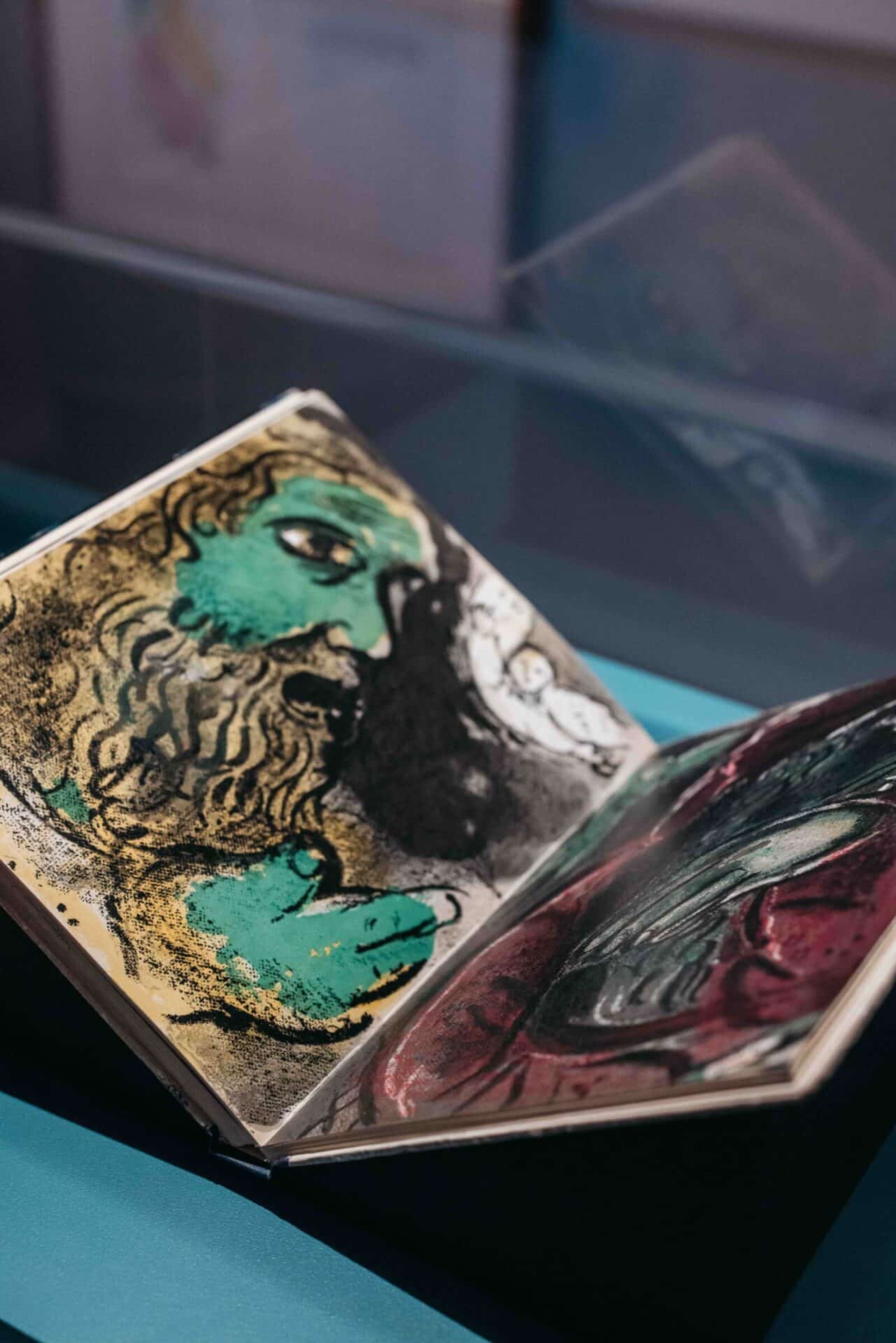

The Bible Series

Marc Chagall’s Bible Series (1931–1939; 1952–1956) took 25 years to complete and comprises two volumes of 105 etchings. Produced at a heightened period in European history, on either side of the Holocaust, it fuses images of Chagall’s Orthodox Jewish upbringing with the pictorial language of figurative painting and Modernism.

Chagall’s Bible Series explores the Old Testament as a series of historic encounters between humanity and God. Unusually commencing with the creation of humanity not the cosmos, prophets and angels are represented with identifiable human characteristics. This was a daring approach given Chagall’s Jewish heritage, which forbids human representation of the divine.

Chagall is widely credited for creating a new visual language for the Hebrew Bible. In 1931 he visited Palestine for the first time and in 1932 he travelled to Amsterdam to study Rembrandt’s biblical paintings as inspiration.

All artworks from the Bible series presented in CHAGALL are from the 1952–1956 period. These compositions are more confrontational and human-like than the earlier series, as Chagall grappled with the atrocities of World War Two. An original copy of the Bible publication, on load from the State Library of Victoria, is shown in the exhibition.

The artist recalled in later life:

“Ever since early childhood, I have been captivated by the Bible. It has always seemed to me and still seems today the greatest source of poetry of all time.”

Love and Legacy

Chagall’s art and life coincided with monumental events of the 20th Century: Tsarist Russia and the Bolshevik Revolution; World War One and Two; the creative interwar years in Paris and Berlin; as well as the foundation of modern-day Israel and the promise of the American ‘New World’. His journey crossed countless political and socio-economic borders and over an exceptionally long 70-year career, mastered the disciplines of drawing, painting, sculpture, public art and design.

While many of Chagall’s peers were inspired by new technologies and moved away from representations of the human body and spirit; with a concerted effort and a unique creative vocabulary, he sought to represent reverence and the full spectrum of the human experience.

At every milestone Chagall was supported by extraordinary women, starting with his mother, FEIGE ITE and his six younger sisters. His first wife BELLA CHAGALL (née ROSENFELD), their daughter IDA CHAGALL and his second wife, VAVA CHAGALL (née BRODSKY) were educated, well-travelled women, who enabled his success in their irrefutable yet interchangeable roles as muse, manager and mother-substitute.

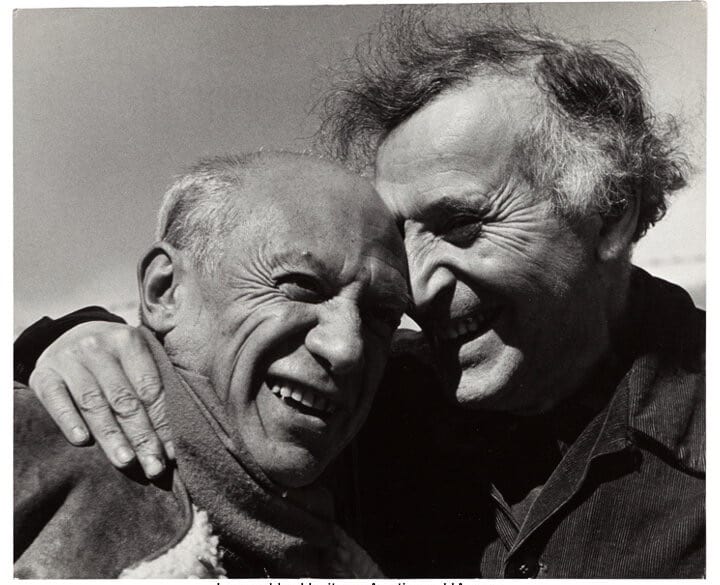

Even his life-long rival, Pablo Picasso conceded:

“When Matisse dies, Chagall will be the only painter left who understands what colour really is…there’s never been anybody since Renoir who has the feeling for light that Chagall has.”

Chagall’s extraordinary life came to an end in 1985 at the age of 97. With no will, which he superstitiously refused to compose, the family panicked at his passing and accepted the mayor’s offer for a site in the local cemetery of his hometown in the South of France.

With little fanfare Chagall was buried. A short speech was delivered by the French Minister of Culture and an unidentified Yiddish journalist delivered the Kaddish (the Jewish prayer for the dead) with no prior approval from the family.

In the absence of a ‘minyan’ (the requirement of at least 10 Orthodox Jewish men to recite prayers), Chagall – arguably the greatest Jewish artist of the 20th Century, hailed from the shtetls of Eastern Europe – was laid to rest in a French Christian cemetery.

Chagall’s legacy was unequivocally ascertained in his lifetime: in 1966 he became the first living-artist to exhibit at the Louvre and in 1973 he received France’s first state-funded custom-built museum dedicated to a contemporary artist. His artworks are prized possessions of major public and private art collections, and his art continues to be exhibited in solo and group exhibitions worldwide.

The arch of Chagall art-and-life story and the reason he is the sole artist to be honoured with two solo shows at the Jewish Museum of Australia, is best explained in the words of Chagall, as he noted in 1982:

“If I were not a Jew (with the content I put out into that word), I wouldn’t have been an artist, or I would be a different artist altogether.”

Credits

This exhibition was made possible with the generous support of all staff, board members, collaborators and sponsors of the Jewish Museum of Australia.

CREATIVE COLLABORATORS

Anna Tregloan, Exhibition Design

Yvette Coppersmith, Australian Contemporary Art Commission

Andrew Renton, Writer and Critic

Giri Brown and Dan Smith at Both Studio, Graphic Design

Michael Burrows at Brand Music, Sound Design

CREATIVE PARTNERS

Alliance Française Melbourne

Art Gallery of NSW

Daniel Besen

Besen Family Foundation

National Gallery of Victoria

Private Lenders

State Library of Victoria

PROJECT TEAM

Jessica Bram, Former Museum Director & CEO

Noe Harsel, Current Museum Director & CEO

Mark Themann, Former Head of Collection and Interpretation

Esther Gyorki, Current Head of Collection and Interpretation

Elisa Ronzoni, Curator of Collection

Lisa Klepfisz, Former Head of Operations

Shelley Krape, Head of Brand and Partnerships

Sarah Giles, Marketing & Communications Coordinator

Liat Azoulay, Brand & Partnerships Assistant

Annette Bagle, Brand & Partnerships Assistant

Theresa Powles, Former Head of Learning & Engagement

Naomi Ryan, Current Head of Learning & Engagement

Alice Freeman, Charlotte Eizenberg, Naomi Dascal, Krystalla Pearce, Learning and Engagement Officers

James Parini, Experience & Facilities Coordinator

PRODUCTION TEAM

Miri Hirschfeld, Project Coordinator

Claire Marmur, Scenic Painter

Design To Print, Graphics Printing

Theatre Star, Curtain Fabrication

Rowan Cochran, AV Tech Support

John Sheehan, George Kyriacou and Joey Kidd-Crowe, Installation Team

Jarrod Burns, Exhibition Build

Marie-Luise Skibbe, Photography

Dan Cahill, Film

Pitch Projects, Publicity