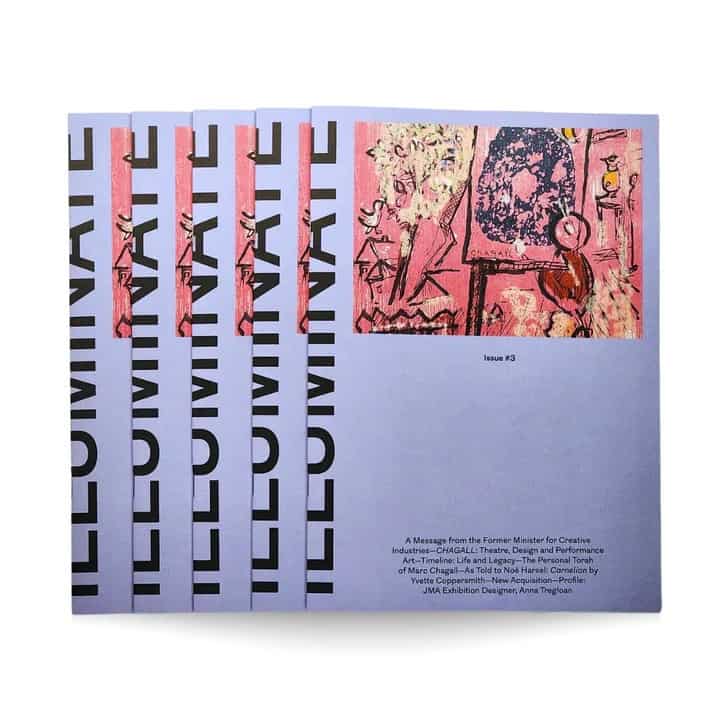

Commissioned by the Jewish Museum of Australia

Published in Illuminate Magazine issue #3 (Spring 2023)

For CHAGALL: Printmaking, Poetry, Public Art

Written by Jade Niklai

In a spectacle of light and colour, CHAGALL showcases the Paris Opera House ceiling, one of the great public art commissions by Marc Chagall. While prestigious and a cultural milestone in a post-World War Two era, its creative roots lay in in the artist’s humble avant-garde experiments in Soviet theatre design and performance art.

Chagall spent World War One in his hometown of Vitebsk where, as a Jew, he was unable to enlist in the Russian army. Following the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, which granted Russian Jews citizenship for the first time, he embraced the new Soviet spirit as Director of the Fine Arts School and as Cultural Commissar of Vitebsk.

Between 1919 and 1920, Chagall organised 10 comedy performances in the main square to entertain 200,000 Red Army soldiers and to deliver Soviet propaganda. He also marked the first anniversary of the Revolution with a one-day festival held on 7 November 1918, which was a spectacular production. Although few details of the project have been recorded, it is, arguably, his first public art commission.

In just a month, Chagall recruited hundreds of housepainters, builders, housewives, the young and the old—and turned Vitebsk into a public art performance. Seven arches were built in the main square, 350 large posters and countless banners and flags were hung from facades, trams and shops. Adorned with Chagall’s imagery, every surface of Vitebsk explored themes of joy, colour, movement and victory.

Motifs in the artwork included a revolutionary tuba player galloping on a green horse, multi-coloured upside-down animals and a militant peasant holding a house in his arms to reflect the new rights of property ownership for common people. A night procession was accompanied by red banners illustrated with the revolutionary symbol of the hammer and sickle. The townspeople’s precious white tablecloths and bedsheets were adorned with Chagall’s art and similar to a Baroque procession, vignettes of the Revolution were performed on the streets.

These productions were likely informed by Chagall’s earlier experiences in Paris (1910–1914), from where his exiled friends were presenting at the same time, Dada performances at Zurich’s Studio Voltaire. The festival was also influenced by his education with Léon Bakst in St Petersburg (1906), the stage and costume designer of many successful Ballets Russes productions in pre-war Paris. Despite public support and the success of the projects held in Vitebsk, political leaders were confounded by Chagall’s bold performance and fired him immediately.

Disillusioned with politics and art administration, Chagall moved to the Moscow Jewish Theatre (1920–1922) where he designed the costumes and stage sets for three pantomimes about Yiddish provincial life. This was a state funded effort to demystify provincial Judaism (the majority of Jews at the time only spoke Yiddish) as the new Soviet society sped towards secularisation and urbanisation.

Over the space of six short weeks, Chagall produced a masterpiece of seven monumental artworks. A seven-metre-long canvas of geometric forms and large floating figures hung from the ceiling, while four easel paintings adorned the stage and explored the themes of music, dance, drama and literature with depictions of Jewish archetypes, including a green-faced violin player, Chassidic wedding jester, marriage broker and Torah scholar.

The backdrop was a still-life composition of cake, fish, fowl and fruit painted in bright pink, violet and ultramarine. Given the theatre’s modest scale and Chagall’s grand vision, the auditorium was engulfed in his aesthetic and the project was quickly dubbed Shagalovsky sal which affectionately translated to English as Chagall’s Box.

The work was a masterful display of artistic vision, Jewish heritage and European modernism. Despite its critical and popular success, Chagall’s Box was seen by the jealous director and disapproving state representative as too decadent and individualistic for the frugal Soviet times. He was not paid and once again let go.

Unknowingly, Western theatre goers became greatly familiar with this work as it served as an inspiration behind the Broadway musical Fiddler on the Roof (1964). The show’s designer had been Chagall’s assistant at the Moscow Jewish Theatre and was deeply moved by the work he had witnessed. Chagall’s Box was the sole purpose for the artist’s final visit to Russia in 1973, when he returned to view the restored canvasses. Chagall regarded this work as one of his great masterpieces and it indeed laid the foundation for a bold practice in theatre and public art.

While exiled in America during World War Two, Chagall returned to the stage with his spectacular designs for the scenography of the New York Ballet Theatre’s production of Aleko. Based on a Alexander Pushkin poem with music by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, the production’s roaring success led to its tour in Mexico City (1942), where the artist Diego Riviera was so taken by Chagall’s vision, it is said to have led to his own forays in stage design.

Despite refusing to speak English, Chagall continued his re-invention as a critically acclaimed theatre designer in America. His iconic work for The New York Metropolitan Opera’s production of Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro (1966–1967) realised 13 curtains (each measuring 20 metres high), 26 partial curtains and 121 individual costumes. For 27 consecutive years it was the star attraction of the annual artistic program and accompanied by two nearby public art commissions: the oil paintings, The Sources of Music (1966) and The Triumph of Music (1966), which adorn the main entrance of the Lincoln Centre Plaza and can be seen from the street front.